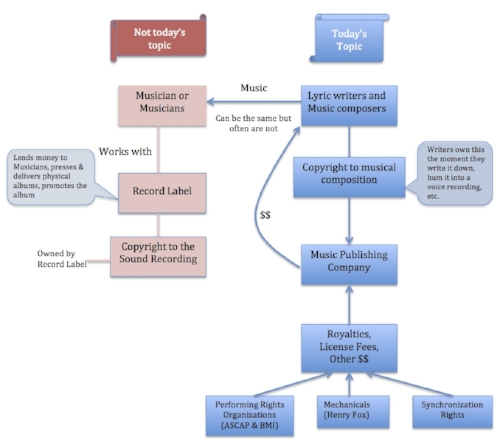

Copyright law splits copyright ownership for music into two sets of rights: 1) rights to the sound recording (the finished product you listen to on Spotify), and 2) rights to the underlying musical composition (the words/beats/chords written on paper). When a songwriter creates a song and ‘fixes it in a tangible medium,’ like writing it down, they get an immediate copyright in that song. But when musicians record that song in a studio, the musicians get a different copyright for the sound recording itself. This split exists for a variety of reasons, but it comes down to the fact that musicians and songwriters have historically been different people.

When the songwriters create that song they get a second right in addition to the copyright: they also become the song’s publisher. A copyright owner is the only one that can decide how their work gets used, and a publisher’s job is to get other people to use a song for money. Because the songwriters are the only ones that can give others a license to use the song, they automatically become the publisher for their song. While a songwriter could handle publishing administration for their song, in reality the logistics would be so intensive that the writers wouldn’t have much time to make music. This is where a publishing company comes in.

A music publishing company is a company that makes sure songwriters and composers get paid when their compositions are used commercially. More specifically, the publishing company has the songwriter assign their copyright in a song over to the publishing company, so that the publishing company can “administer” the copyright and get people to use the song commercially. The publisher provides song licenses to users, and they make sure that everyone gets paid when due for different types of royalties, like performance rights, mechanicals, and synchronization rights. While each of these is a valid source of funds, performance rights are really the most important for a newer artist as they allow the songwriter and composer to get paid every time their music is played on radio stations, on television, in restaurants, or in live venues.

As funds come in from the various songwriter and performance royalty outlets the publishing company splits revenues with the songwriter. Unlike with royalties that the whole band might receive from income on an album, royalties and payments from the publisher are on a per-song basis because each song can have different writers. Each writer or composer of a song can have their own publisher, and that publisher can either administer an individual song, or all of the songs that a writer creates.

With background out of the way, follow these guidelines to

START YOUR OWN MUSIC PUBLISHING COMPANY

1. Decide on a name for your publishing company

The name you use is important for two entities you’ll be dealing with: the state in which you will create your company, and the Performing Rights Organization (“PRO”, explained in point 3 below) that you’ll register with. It’s a good idea to search for any name you decide on because the state and the PRO, while unrelated, will only let one entity use a specific name. The PROs don’t want to accidentally pay the wrong company, and the state doesn’t want consumers to get confused. Most states have an option to search their databases to see if a name is in use. DC has a preliminary search option here, and CA has one here. For the PROs, you can start filling out an application on their website (below) to get an idea on name availability.

As a tip for both, you want to use something that isn’t common or plain—add a little flair because you need to make it unique in order to register. “Rap Music, Inc.” might not pass, but “Flow Gawds” probably will.

2. Create a business entity

Every business that operates in a state needs to be registered in that state. Others may suggest that you sign up with a PRO first, but there are two reasons to create the business earlier: 1) The registration pages of the PROs require your business name and federal Employer tax ID number (EIN), and 2) having a registered business in place for your operations can shield you from liability.

In the worst-case scenario that your business name gets taken in the PRO while you’re registering your company with the state, you can set up a trade name or doing-business-as name with the state for a different name that might still be available with the PRO.

Once you’ve created the business entity you’ll need to get a EIN number here, and you’ll also need to use this paperwork to open a business bank account and/or to cash checks made out to you as a publishing company.

3. Affiliate with a PRO

A Performance Rights Organization collects performance royalties on behalf of songwriters and publishers by making agreements with commercial venues that play music. They make sure that restaurants, malls, radio stations, and dance clubs pay for their use of someone else’s music, and then they pay the publisher and songwriter their shares. The major performing rights organizations in the United States are Broadcast Music, Incorporated (BMI), the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), and SESAC, which dropped its long-form name in 1940. In order to get paid by the PRO, the writer and the publisher need to register with the PRO.

While Publishers can register with all of the PROs, writers can only affiliate with one. If you’re starting out as a publisher, it only makes sense to register with the one or ones where the writers you are representing are registered. For example, if both of the writers above are with ASCAP, then you only need to register with ASCAP for now. If one is with ASCAP and one with BMI, and you plan to represent both writers and their shares in the song, then you’ll want to register with both.

Of note, writers can only become members of SESAC by invitation, so unless you’ve got a deep connection with a big name writer before you start your publishing company, you’ll probably be keeping it to ASCAP or BMI in the early stages.

For ASCAP, you can register at www.ascap.com, or here. The application fee is $50 for publishing companies.

For BMI, you can register at www.bmi.com, or here. The application is $250 for corporation, partnerships, and LLCs, or $150 for individuals—but if you take one piece of advice from this post, it’s this: please create a company for this process, don’t proceed as an individual. There is no limitation to your liability as an individual. If you’ve got questions on this feel free to reach out to Hardeep at HG@tresquire.com, or look out for further posts.

4. Make sure you know exactly who owns each song, and have the writers assign you their copyrights.

While a songwriter may claim that they wrote a song and have full ownership, it always makes sense to ask a few questions. Did anyone help write the lyrics? Is there a manager, a friend that came up with the hook, or someone that donated space to write the music that might make some kind of claim to ownership? Did the songwriter make an agreement with any other writers on who owns what portion? Absent an agreement to the contrary, US Copyright law assumes that everyone that helped create a song owns an equal share.

Next, you need to determine what kind of relationship the writer or writers you represent are looking for. Do they want an exclusive agreement whereby you publish every song they’ve made thus far and every song they’ll make for the next seven years? Do they just want you to handle this one song? Is it somewhere in between? Either way, you’ll want to have an entertainment attorney create an agreement between you and the songwriter(s) that clarifies rights, responsibilities, and royalty shares, and another quick agreement that assigns their copyright over to you as the publishing company so that you can administer the songs. And before anyone starts worrying about the publishing company stealing ownership to the music, the reason for this transfer of ownership is so that the publisher can build a large catalog of music. The larger their catalog, the larger their market power, and the more likely you are to get your music pushed. But also, watch out for people stealing your music.

5. Register songs with the Copyright Office

Once the songs have been assigned to you, you’ll need to register the songs with the United States Copyright Office in your publishing company’s name. If the song was already registered in the writer’s name, you’ll need to file an assignment transferring them to your publishing company’s name. You can login to the Electronic Copyright Office Registration System here, and more information is available at https://www.copyright.gov.

6. Register songs with the PRO

If you didn’t already do this, register each of the songs with the Performance Rights Organization that the writer is affiliated with. If you’re representing two writers for the same song and they each are affiliated with a different PRO, you’ll want to register the song with both of them.

Bonus: Find an international administrator

All of the above information is for administration and publishing in the United States. If the writer you’re representing or the song you’re publishing has international appeal, you’ll want to find an international administrator for publishing in other countries, as each country has their own methods and requirements for publishing music.

****Fun fact, this post is protected by Copyright law, so please don't steal it without asking